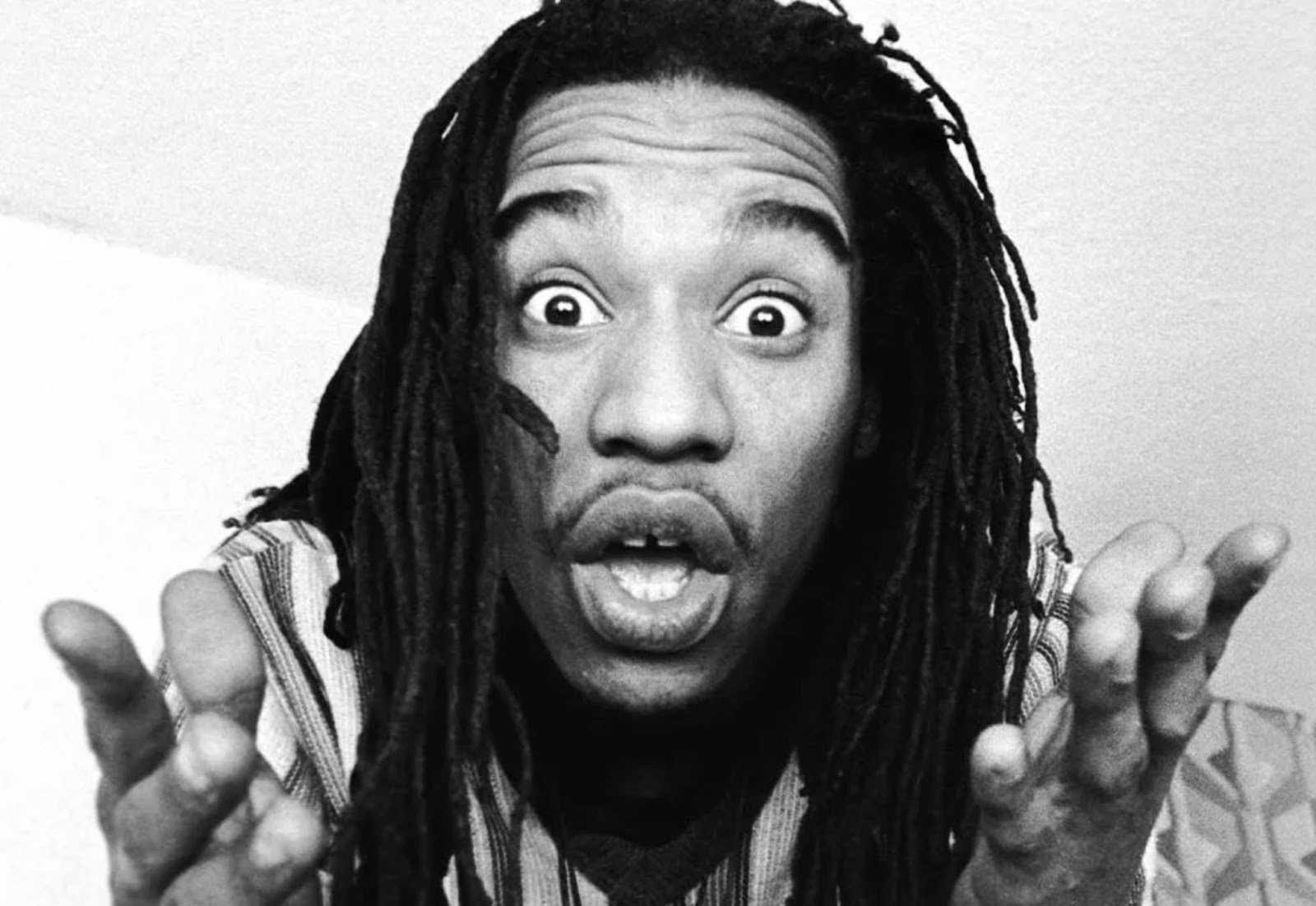

Benjamin Zephaniah was a poet, writer and activist whose voice has remained an important part of the British cultural landscape for decades. As one of the active participants in the dub poetry movement, a form of poetic recitation that emerged in Jamaica in the 1970s, he used his art to fight racism, imperialism and social injustice.

An interesting fact is that his principles were put to the test in November 2003, when Her Majesty the Queen of the United Kingdom offered Benjamin the title of Officer of the Order of the British Empire. This event made the front pages of national newspapers, but Benjamin Zephaniah publicly declined the honour, writing a scathing article in which he explained that the word “empire” reminded him of slavery and cruelty. Read about the life and work of the Jamaican-born Birmingham resident, his poetry, resistance and principles at birminghamski.com.

Unfinished school

His refusal of the Order of the British Empire sparked widespread national debate in the local press. At the time, much was written about the British award system and the legacy of colonialism. Instead, Zephaniah’s legacy is defined by his honesty and unique ability to always speak the truth to everyone, including those in power, thanks to which he remains a symbol of resistance and artistic genius.

Benjamin was born in Handsworth, Birmingham, on 15 April 1958. The writer called this area the Jamaican capital of Europe. Due to dyslexia, he dropped out of school at the age of 13, unable to read or write. At the same time, he read reggae poems in church from the age of 10–11.

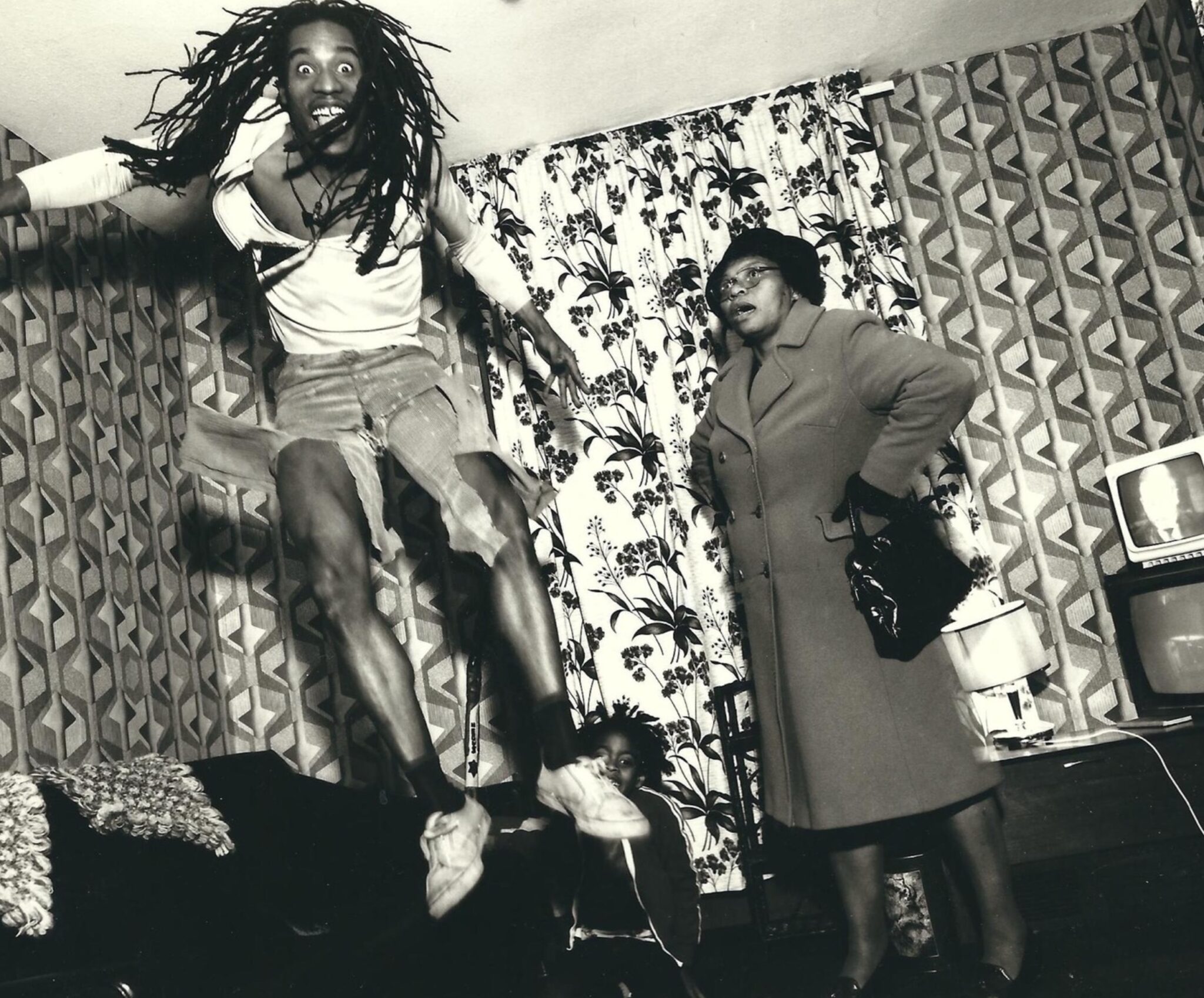

Benjamin Zephaniah never wanted to be a salon poet. His poetry was born on the streets, amid the noise, anger and music of Birmingham. Born in this large industrial city in the Midlands, he grew up in a Britain where racism, unfortunately, had not yet been completely eradicated, nor had social inequality and the legacy of colonialism. As a result, the young man realised quite early on that words could be a form of survival, as well as a form of struggle.

Coming from a Caribbean family, Zephaniah grew up in an environment where school was not a refuge but a place of symbolic violence. Dyslexic, misunderstood, often punished rather than encouraged, he left school without a diploma. Later, in an interview, Benjamin recalled that school told him he was stupid, but poetry proved the opposite. This early exclusion shaped his deep distrust of institutions and his strong commitment to self-education.

Street culture

At the age of seventeen, Benjamin left Birmingham and moved to London, driven by the simple conviction that his silence would be a form of betrayal. In the capital, he gradually became one of the leading representatives of performance poetry. At a time when British poetry remained predominantly white and academic, Zephaniah championed the vernacular, imbued with the unique linguistic hybrids of Creole that emerged during the colonial era, slang and music. The poet sincerely believed that poetry should not be the privilege of the elite. He wanted it to belong to people who had never opened a poetry book.

Benjamin Zephaniah’s first significant collection, Pen Rhythm, laid the foundations for his work. It is about exposing racism, criticising police violence and defending the oppressed. His texts were broadcast on the radio, in schools and in prisons. Zephaniah became a public poet, a poet of the stage, who was sometimes listened to more than read — and he was proud of this, claiming that if his poems were shouted out on the street rather than whispered in a library, then he had achieved success.

Fame and popularity

To say that Benjamin Zephaniah’s popularity grew in the 1990s is an understatement. It grew significantly. With his new collections, such as Too Black, Too Strong and Propa Propaganda, Benjamin established himself as the political conscience of contemporary Britain. However, he refuses to be seen as just a poet-activist. His work also explores tenderness, childhood, fear, love, and vulnerability.

This aspect is clearly evident in his children’s collection Talking Turkeys, which unexpectedly became a bestseller. Under the guise of lightheartedness, Zephaniah promoted respect for living beings, vegetarianism, and empathy. He also talked to children because they listened to him, unlike adults, who often closed their hearts.

In parallel with poetry, Benjamin Zephaniah turned to novels. One of them, Face, tells the story of a teenager who was maimed during an attack, who faces the views of other people and wants to be reborn. The book was a huge success in British schools precisely because it appeals to young readers without condescension. Zephaniah demonstrates that literature dealing with social issues can also be deeply human.

Benjamin positions himself as an anti-racist activist, animal rights advocate, and radical critic of colonialism. Despite this stance, institutional recognition eventually comes. Benjamin Zephaniah receives several honorary doctorates, and his works are included in school curricula. The University of Birmingham pays tribute to him, albeit belatedly, recognising the son of the city that once rejected him at school. This recognition is unlikely to heal the wounds Benjamin suffered in childhood when he was forced to leave school, but it symbolises a form of compensation.

On a personal level, Zephaniah lives a life true to his convictions. A vegan who is close to nature, he describes himself as a poet in motion, dividing his time between writing, music, meeting young people and travelling. Birmingham remains his emotional anchor. The poet admits that although Birmingham broke him at one point, it was the city that gave him his voice.

The death of a poet

On 7 December 2023, Benjamin Zephaniah passed away, leaving behind a body of work that lives on. His poetry does not seek to appease; it awakens, disturbs and sometimes comforts. It reminds us that literature can be an act of resistance, a gesture of love and a way to remain human in this unjust world.

Born into a family of immigrants, he overcame dyslexia and racism by turning street politics into poetry. He wrote many works, starred in films, actively defended animal rights, and was considered the voice of British multiculturalism. Benjamin Zephaniah never asked for permission to speak his mind. And that is why his voice was heard.

Sources: